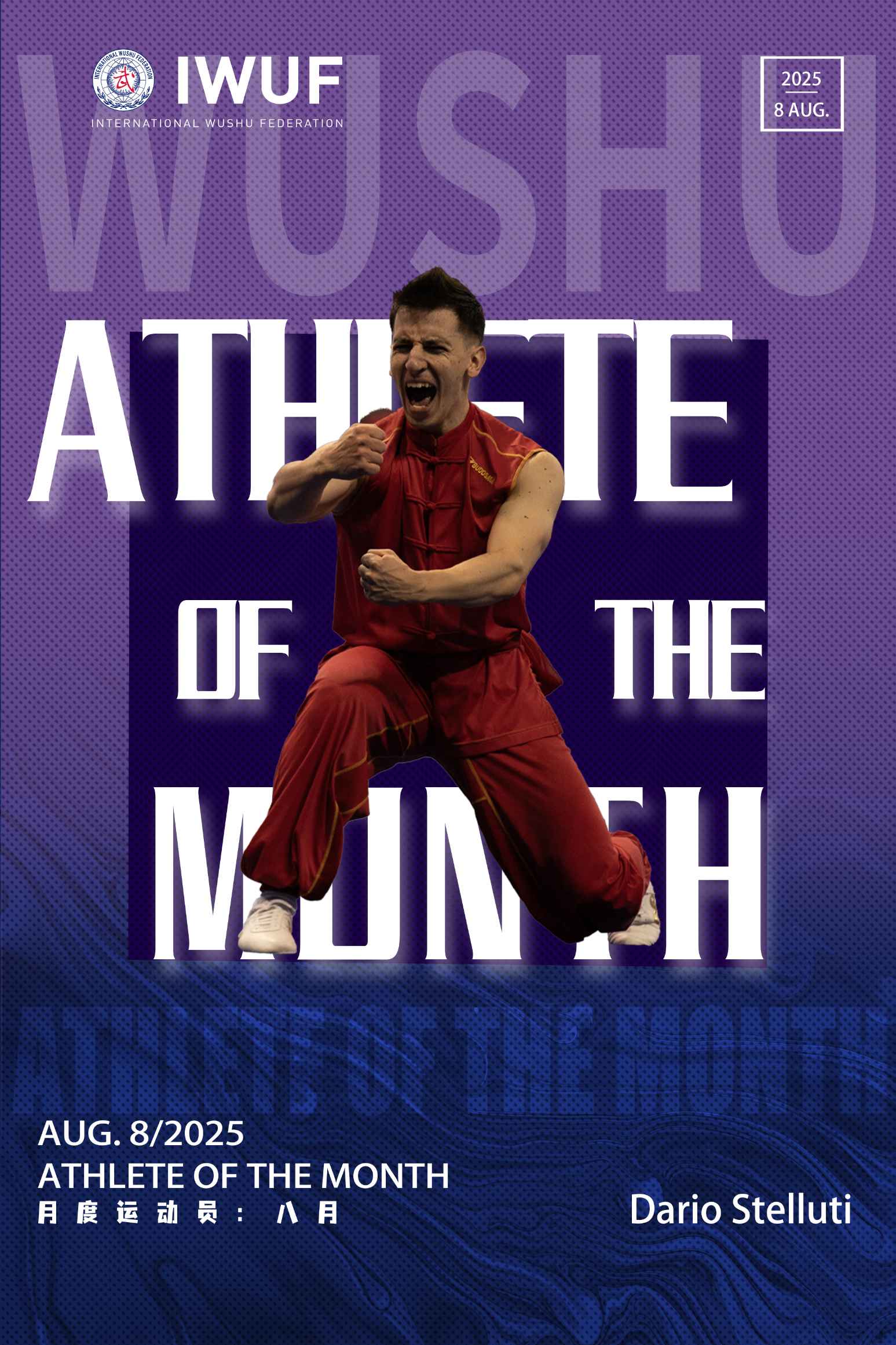

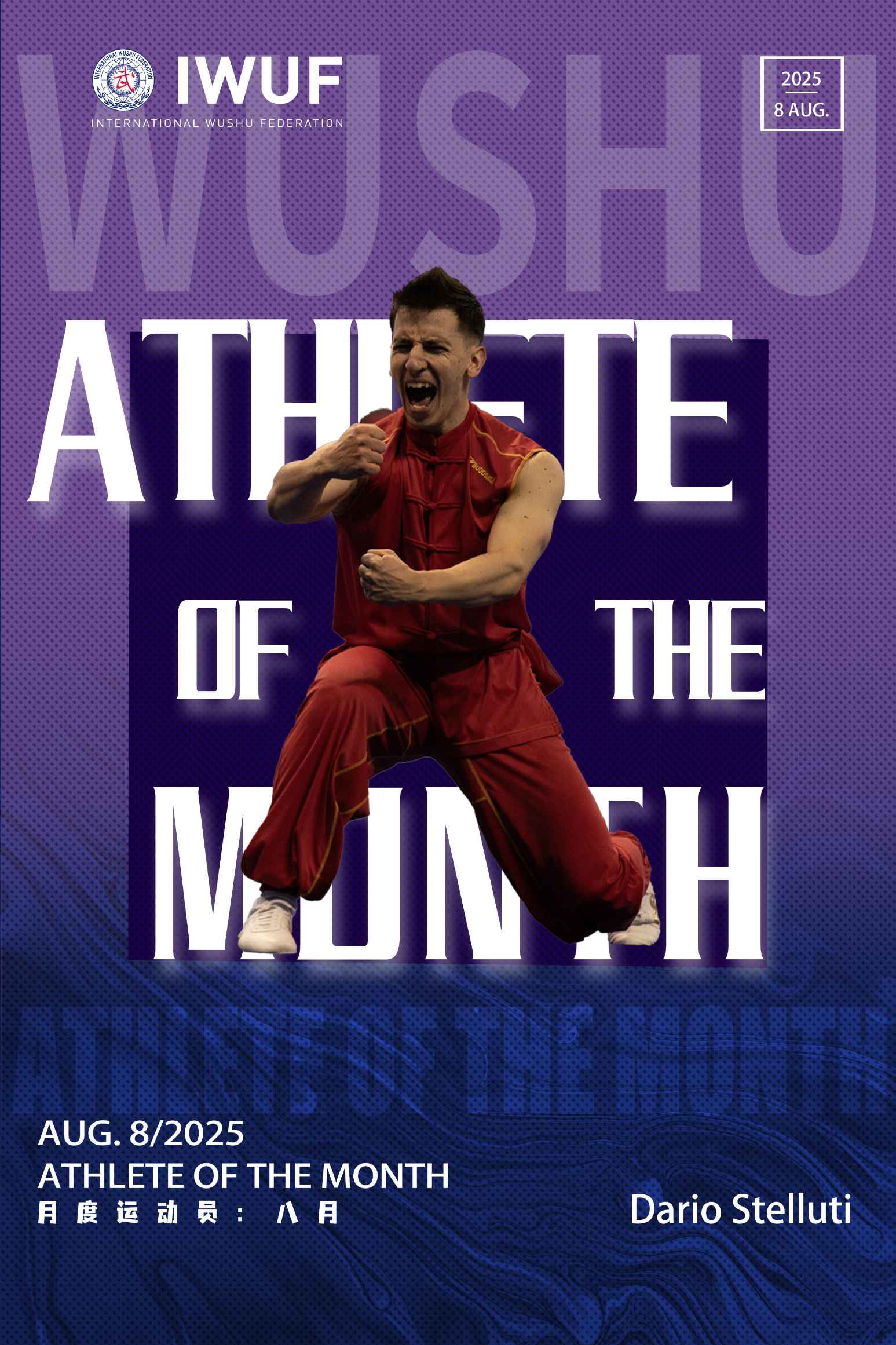

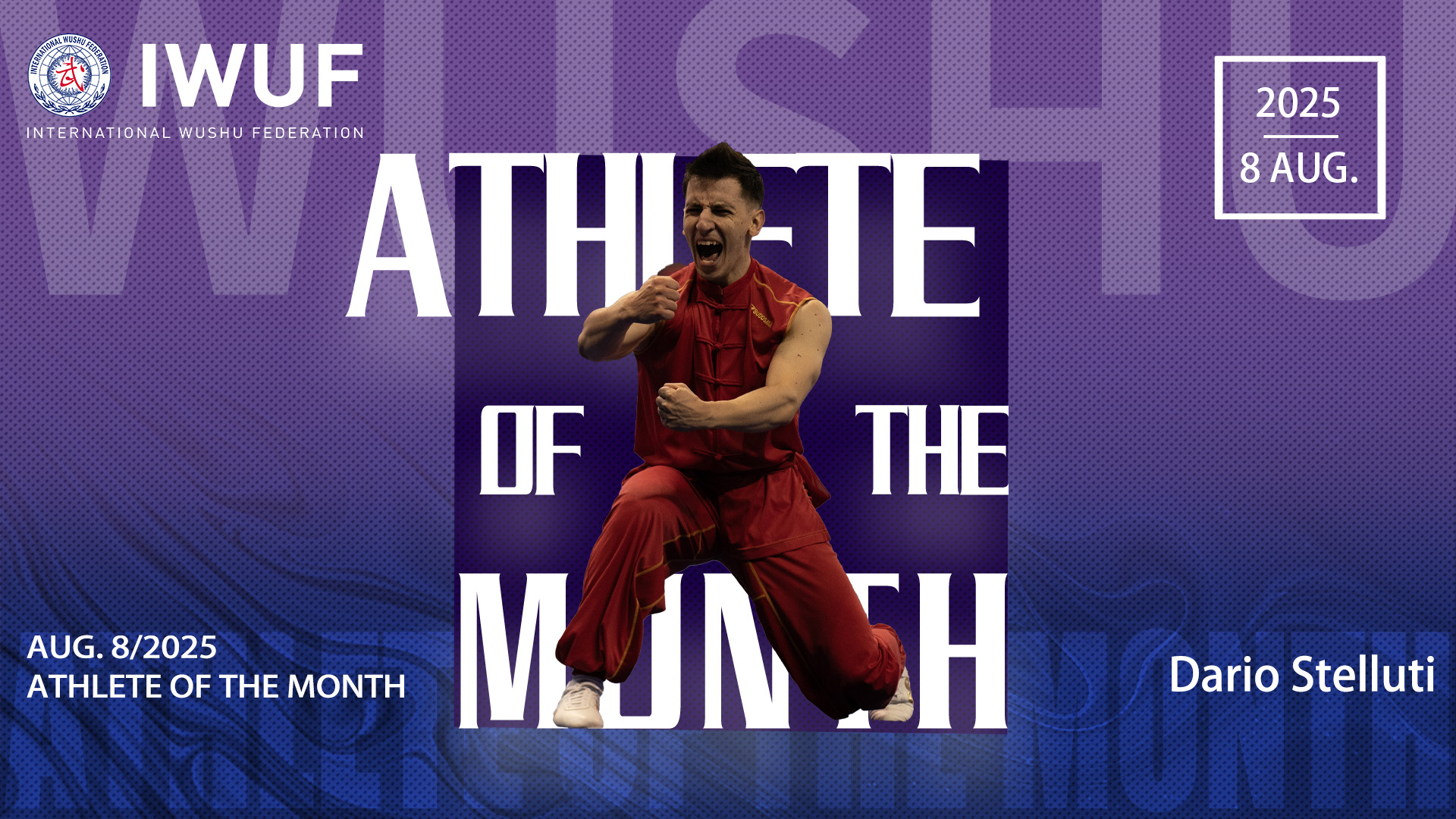

Dario Stelluti began practicing wushu in 2008, and for the first three years he trained in secret, as his parents had envisioned a different path for him. After achieving success at the national level, his breakthrough came at the 2nd Wushu Mediterranean Championship in 2019 where he won a gold medal in nandao/nangun/nanquan. Since then he has represented his country at major international events, including the 15th and 16th World Wushu Championships (placing 14th and 12th respectively), the 19th European Wushu Championships where he placed 1st in nangun, and the 3rd Taolu World Cup in 2024 (placing 5th). He placed 3rd in The World Games Series in Hong Kong, China in 2024 and in August competed at The World Games 2025 in Chengdu. Dario has worked energetically to spread wushu’s values and visibility through innovative means, hosting a streaming show where he analyzes matches with his audience, promotes ethical sportsmanship, and builds a growing community. Through his sponsorship with Adidas, he notes wushu gained corporate visibility. His parallel career as a stuntman allows him to bring its movements and values into the world of cinema, promoting discipline, teamwork, excellence, and the global promotion of martial arts.

Wushu Beginnings

Italian athlete Dario Stelluti, 31, discovered wushu at a very young age. He remembers that on weekend mornings he would watch lots of movies during breakfast. “My favorites,” he says, “were always Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee films — they were my constant companions. That’s how I first came into contact with wushu, and I fell in love immediately. I started practicing at 12, with a free one-month trial. I came back the following year, and again the year after. But it wasn’t until I was 14 that I started attending classes regularly, dedicating myself to daily training.”

Like many kids, Dario recalls that, “What fascinated me from the start was how wushu practitioners seemed like superheroes, almost as if they had real superpowers. This sport unlocks each person’s potential and elevates it beyond that of the average human. The jumps, spins, flexibility, and speed of the athletes are extraordinary. I believe all of this comes from the sense of freedom that, for me, only wushu can convey every time I practice it.”

Training in Secret

Dario, however, was compelled to train in secret for the first three years due to his parents’ opposition. He was studying karate at the time and they saw that as their son’s future martial art path. “My parents were against it—they wanted me to continue with karate,” he recalls. “This was due to a misunderstanding, stemming from their inexperience and the general lack of martial arts knowledge in Italy at the time. Back then, karate was often considered synonymous with all martial arts, regardless of origin. When they took me to a class, I immediately knew it wasn’t the martial art I wanted. Unfortunately, there weren’t accessible alternatives for a child just under 8 years old: the internet wasn’t what it is today, social media didn’t exist, and the term “wushu” was completely unknown. People still used “Kungfu.”

“So,” Dario recounts, “my parents insisted I continue with karate. When I finally gained some independence to explore the city and find a wushu class, they told me I first had to complete my karate journey up to a black belt. Only then could I switch disciplines, if I wanted, even though that didn’t mean they agreed. Against all odds, not only did I quickly earn my black belt, but I became even more motivated to practice wushu. The brief experience from the previous year wasn’t enough—I needed to fully immerse myself in it. My parents insisted I “mature” with the black belt, to see if my love for wushu was real or fleeting. I was furious: I knew from day one that karate wasn’t for me. Too rigid, too strict, too far from who I was. One wushu class had taught me more than years of karate—not because karate was useless, but simply because it wasn’t the right art for me. So I secretly continued attending wushu classes during the free trial month—it kept the fire inside me alive, ready to blaze the following year. Karate classes felt slow; nothing challenged me, and I could apply the few principles I’d learned in wushu to excel.”

Dario was forced to learn another discipline as well -- patience. “A year passed,” he recalls, “and my parents still opposed it: they told me to wait through the summer and then talk to the sensei to see if I had the courage to make the decision I had already made on the first day. I kept attending wushu secretly over the summer, promising myself nothing would stop me from joining fully. It was 2008, the year wushu was supposed to enter the Olympics. That summer, I called my sensei and told him how I had felt for years. He tried to convince me (unsuccessfully) to practice a simpler, related martial art because wushu was too difficult. But that’s exactly what drew me: it made me feel myself, capable of anything, and offered the chance to become the person I wanted to be. I ended the call thanking him for his teachings but making it clear my path was changing and I couldn’t wait any longer.”

Early Years of Wushu

Dario looks back on the competitive wushu landscape in Italy like at the time as he was training, growing, and competing. “In my early years of wushu practice,” he says, “Italy was still recovering from a flourishing period of competitions and many registrations. I remember watching wushu at the Beijing Olympics (not officially, but in a parallel event with a famous story), and Italy’s pride was Michele Giordano, who represented the country in that competition. I went from being a rising talent in karate to being a complete unknown in wushu. Arrogantly, I thought my karate experience would let me beat anyone. After a year of training, I believed the sky was the limit. I couldn’t have been more wrong: I wasn’t even ready to join my team’s competitive squad, let alone beat Michele Giordano or anyone else.”

Dario continues, “I had to learn to properly use competition shoes while the team executed acrobatics and routines beyond my imagination. I struggled to enter the national competition team. My sifu had set strict requirements, and I was determined to prove my worth and keep my fire alive. At my first competition, I performed a 16-move form and felt on top of the world after winning. Then I watched other competitions and realized I had only moved a grain of snow on a massive iceberg. From 32-move forms to compulsory, free forms, and weapon forms, I had never seen such long and complex routines. I worked hard, and my body wasn’t used to such sustained effort with extraordinary techniques—it felt unreachable, and I had to push myself to the limit.”

National Gold, Community & International Friendships

Dario began his exploration phase of wushu styles. “Thanks to my background in Japanese martial arts,” he says, “my teacher initially thought I should focus on nanquan, but my sense of freedom and his changquan influence allowed me to practice northern styles too, particularly daoshu and gunshu. My first major successes came the following year, when I won gold at the national championships in daoshu and compulsory nanquan. My failures turned out to be my greatest teachers: every defeat taught me something new. The most important lesson was that my real opponent was myself. It wasn’t about beating others; it was about improving every day, becoming a better version of myself with each taolu. Competitors like Michele Giordano, Arturo Gallo, Farshad Arabi, Shahin Banitalebi, Andrii Koval, Sami Ben Mahmoud, Gabriel Komaziro, and others were not rivals but companions in competition. Once I understood this, I became unstoppable… at least in my small world.

Dario would eventually come to focus on southern styles. “What fascinated me about southern styles,” he remembers, “was their animalistic, brutal side, closer to my Japanese martial arts background. I like to think every southern style practitioner secretly wishes to master northern styles too, especially qiangshu—for me, that’s definitely true. As for nanquan, I consider it the ultimate expression of imaginary, animalistic combat, unlike the more elegant and less fierce changquan. Practicing it is exhausting because it engages the whole body, but it’s just you, your punches, and your kicks… pure freedom. Nangun feels restrictive for me, having practiced gunshu until 2018, while Hougun (monkey staff) is my “secret lover.” Nangun techniques feel a bit limiting, and I’m still exploring ways to make them feel more alive without breaking the style. It’s a gradual process, but I’m determined to contribute to its growth. Nandao is magnificent: its form and simplicity leave me speechless. I’m a fan of great swords, and nandao often makes me feel like a fantasy character. Its possibilities are incredible: you can hold it in reverse, use the ring tip, flip easily thanks to its guard, and wield it with one or both hands without limits. Practicing it is a lot of fun.”

International Debut

Dario’s international debut came at a competition in Türkiye in 2014, when, he says, “The federation finally allowed me to join the Italian national team after years of rejection. It was an amazing experience: traveling the world, no longer just within Italy, with the sole purpose of competing and showing the world “I exist.” From my first year, I had watched national team members on YouTube and other platforms, trying to breathe in the special atmosphere that only international competitions create.”

At the 2nd Wushu Mediterranean Championship in 2019, his second international experience representing Italy, Dario won a gold medal in nandao/nangun/nanquan. “That year,” he says, “I decided never to make mistakes on nandu again, practicing hours in the gym even during university. After 11 years of experience, when sport had become essential in my life, I learned how to enter and exit the flow state at will, inspired by Coach Glen Mills, Usain Bolt’s trainer.”

Experiencing the World Championships

From then on it was onwards and upwards for his wushu career, as Dario would go to compete at the 15th and 16th World Wushu Championships, placing 14th and 12th respectively. He remembers his experiences at these events as exceptional. “My first World Championships,” he says, “was simply monumental: in Shanghai, the international federation organized everything on a grand scale, almost like the Olympics. However, during team training, we couldn’t try the competition mat, which led to mistakes I’d never worried about before. Thanks to my coach, we adjusted daily during the competition, avoiding repeated errors and eventually achieving top scores. The second World Championships, held four years later due to COVID-19, felt surprisingly similar: time seemed frozen, and I picked up right where I left off, improving my scores each day.”

Meanwhile, back on his home continent of Europe, Dario continued to up his game, and at the 19th European Wushu Championships he placed a golden first in nangun. At this event, he says, “I learned crucial lessons. The competition was amazing, and even though I competed in two events almost simultaneously due to scheduling, I realized that nothing should disturb my focus. A bad draw, distracted judges, extreme travel, cold, heat, or grief… nothing could stop me from performing at my best. When I stepped onto the mat, for that one minute and 30 seconds, the world and its problems disappeared—I felt free.”

Taolu World Cup to The World Games

Dario would learn to translate this focus and freedom to the smaller, elite competition of the 3rd Taolu World Cup in 2024 where he placed 5th. “I loved competing in the 3rd Taolu World Cup,” he says. “The audience was incredibly warm, and I enjoyed giving a performance different from what they expected from the other, more athletic competitors. I loved challenging myself against athletes with more experience and skill… I thrive as the underdog, proving that my fire can burn too.”

In 2024 he also placed 3rd in The World Games Series in Hong Kong, China, putting Dario on the path to the World Games 2025 in Chengdu. “The Hong Kong competition was unexpected and emotionally full of surprises,” he says, “starting from the journey to the venue. The event was well organized and provided everything an athlete needs to perform at their best. I’m very happy with that competition and how other athletes also reached their peak: we cheered, supported, and applauded each other—a beautiful way to experience wushu.”

Then, the following year he was on his way to The World Games 2025 in Chengdu. “Everything was perfect,” Dario recalls, “like the Olympics, perhaps even more. Practicing wushu in China is already extraordinary, but competing in a prestigious event with top-ranked athletes is invaluable. Despite the massive gym, the layout made me feel surprisingly intimate and welcomed on the mat. My first performance had a small computer system error, but we fixed it before the second session. I always remind myself of Coach Glen Mills’ words at each competition: nothing can negatively affect my performance.”

Wushu Life – Friends Beyond Boundaries

Of his many experiences in wushu, Dario treasures friendship and community most highly. He gives an example, telling us that, “One of the most beautiful experiences I remember is a friendship built competition by competition. I competed against Arturo Gallo: we were both young, yet we avoided the negative competition common at the time. We cheered for each other, exchanged advice, and even as kids traveled long hours by train across Italy to train together. We improved together, and when he retired, our friendship grew even stronger. He and his brother Mario helped me develop as a nanquan athlete, sharing knowledge, correcting routines, and offering guidance. I will always be grateful to the Gallo family; this friendship is one of my dearest memories.”

Dario also shares strong friendships with other wushu athletes around the globe, noting, “I am truly grateful to the wushu community for welcoming me, and I gladly return the friendships I build day by day, competition by competition, with other international athletes. We live in a fascinating era where technology allows us not only to stay in touch with people thousands of kilometers away but also to communicate in multiple languages. During COVID, the global wushu community grew even closer, and I put myself forward to help break down barriers and preconceptions. I remember practicing nandu at home while messaging Shahin in Farsi for advice, or when Koval sent me audio in Ukrainian to improve my pantui. I enjoy learning languages because it helps me quickly make friends. During competitions, I focus completely, only letting loose after my events, showing two very different sides of “Dario” to teammates and other athletes. It’s amazing to see how everyone shares the same mood, understanding and respecting each other’s boundaries and routines, waiting for the right moment to reconnect as friends. The friendship among athletes is “suspended”: we may not see each other for months or years, but when we meet again, it feels as if no time has passed. I think about them every day, wondering if they’re training at that moment too; often, that thought motivates me when I don’t feel like training. Technology is on our side, and bringing my vlog camera to each competition allows me to capture precious memories to share with the world.”

A Life and Philosophy in Pursuit of Wushu

Dario considers the wushu school he attends and his coach, Marco Alfinito, as part of his family. “I consider the gym my second home,” he says, “and from the beginning, I was the first to arrive and the last to leave. Today, I have a gym in my house, where I live, eat, sleep, and breathe every moment in that magical environment. My coach knows everything about me, gives the right guidance, and allows me to make my own choices, even to make mistakes to learn from them. At the same time, he’s always supported me when I needed extra guidance.”

“I went to China alone,” Dario continues, “following one of the coaches from Beijing Sport University, and I continue to travel worldwide, seeking advice from anyone who can help. Even a single word can improve me, and I am willing to do whatever it takes to hear it. My coach holds the most important place in my training and life as an athlete, but everyone has a space in my heart. On the competition mat, I feel their hands on my shoulders, reminding me of their teachings. I carry all of them with me, and every movement reflects what they have passed on: I’m not alone on the mat… we’re all there.”

Dario tells us that thanks to scholarships during school and university, he was able to buy a small house, which he turned into a proper gym. “Often,” he says, “late at night, I get ideas for a film or a taolu: practicing immediately lets me sleep peacefully. Given my life as an athlete in Italy, I balance work and training, with three-hour breaks for targeted sessions depending on the day or time: muscle conditioning, posture, technique, plyometrics, nandu, jibengong, or taolu, multiple times a day. I usually train two to three times daily. My degree in Sport Science and exchanges with trainers from other sports and countries help me optimize and constantly improve my training.”

Wushu in Italy

We asked Dario how he sees wushu developing in Italy in the next decade, and what are the biggest challenges, and biggest achievements? He has definite thoughts on the topic. “I hope to contribute to the growth of wushu in Italy in the coming years,” he states. “I have many ideas and enjoy surrounding myself with people who share the same dream and can contribute their vision. We definitely need to invest more time and effort in supporting athletes: we must keep their spark alive without abusing their patience. The world has become fast-paced and disposable, but wushu cannot be treated the same.”

“My proposals for the sport’s development,” Dario continues, “include seminars, gatherings, training, tests, and other initiatives, aiming to create in Italy what other sports have achieved years ago. If politicians won’t act, we must give athletes the freedom to organize themselves without feeling “guilty.” For too long, martial arts have been dominated by gurus and insurmountable dogmas. I believe it’s time to move beyond the old “I know everything, there’s no other master” system—often theological in nature—and adopt a more academic approach, where an open mind, curiosity, and knowledge-sharing drive the process. Every time I hear about Wushu at the Olympics (even youth olympic games), my heart fills with hope, not just to make wushu known worldwide but also to develop it within each nation. I hope national Olympic committees will increase their interest and implement consistent quality controls, managing wushu as professional sports are managed. I hope my Italian brothers and sisters are ready to show the world that “we exist too.”

Challenges and Rewards

Life as a wushu athlete in Italy, says Dario, is the greatest challenge an athlete can face. “No practitioner can afford to live solely for wushu or train all the hours needed to be competitive like a professional athlete,” he notes. “In Europe, no athlete is paid to practice wushu. From school—which often treats sports as a hobby rather than a path of personal development or a career—to friends who don’t understand the sacrifices, to work, which in Italy is not seen as a real job for athletes, to romantic relationships that may not understand our passion for competing… these are challenges I face daily. On top of that, I’ve had to overcome personal hardships: complex family situations, financial difficulties… everything imaginable. But this is life, and nothing can negatively impact my performance.”

Dario musingly adds, “The most beautiful part of being a wushu athlete is performing feats beyond human comprehension: supersonic spins, gravity-defying jumps, punches and kicks like lightning and thunder, the calm before a one-minute-and-30-second storm. Traveling, knowing exactly what you’ll do, watching ordinary people and wondering if they know such an extraordinary sport exists… it makes me smile, feeling like I’m the only one on the plane who can do what I do. I feel like Superman as Clark Kent, or Spider-Man as Peter Parker. When we’re in the team, comparisons to the Justice League or the Avengers are inevitable. The post-competition party is the best part: everyone relaxes, rankings don’t matter, and everyone is friends. For one night, no one thinks about wushu, yet we all can’t wait to get back to it. One evening at the after-party of the 16th World Championship stands out: making everyone laugh, playing, talking, and bringing everyone together at one table was my greatest satisfaction. I may be a “nobody” athletically, but in that moment, anyone watching could smile.”

Building Community, Promoting Wushu

Dario hosts a streaming show about wushu, and his strategy to build a community, all while promoting the development of Italian wushu, fills him with enthusiasm. “What I do for wushu comes naturally, driven by my love for the sport,” he says. “During my live streams, I try to challenge rigid judgments and outdated ideas that have caused many to leave wushu. I love laughing and making others laugh, creating a friendly environment where mistakes in taolu bring shared amusement—but always with respect. Judges are serious; we spectators just want to enjoy the show, laugh, and be moved. Soon, my streams will be in Italian and English, promoting wushu beyond Italy. Although this may reduce views, I trust the global community’s support. Vlogs, which I’m still learning to edit, are excellent for reaching more people and creating lasting content. I aim to become one of the faces of wushu in Italy and worldwide, promoting the sport and the friendship it fosters, breaking political, religious, cultural, war, and epidemic barriers.”

Dario also has a sponsorship deal with Adidas. “My relationship with Adidas is the result of a long-term project,” he says. “and I hope it will allow me to use it as a powerful promotional tool. I’m not authorized to disclose details, and given wushu’s limited popularity in Italy, progress is slow. One of my personal strategies is to grow the community and followers, increasing leverage and financial freedom to promote wushu globally.”

Career as a Stuntman

A neat parallel to Dario’s wushu career is his professional work career as a stuntman, where he sometimes gets to showcase his wushu prowess in front of the camera. “My career as a stuntman could fill an interview as long as my athletic career,” he comments. “My love for wushu comes from martial arts films: before knowing what it meant to be an athlete, I wanted—and still want—to be like the heroes in those movies. That’s why I practice wushu so intensely. It’s my dream: wushu is the vessel that lets me sail the world and spread my fire. I don’t often use wushu in stunt projects, but when I do, it’s visible and appreciated. Wushu makes many parts of stunt work easier: it’s extremely complex, and compared to it, stunt work almost feels like a game. Not all projects are simple, though; it’s the safest work because it ensures dangerous scenes are secure and spectacular. Like all work, risk exists, and sometimes I must pause depending on whether I’m preparing for a competition or a film to protect my health. I am so obsessed with wushu that I bring the same precision to film choreography. Unlike wushu, film work is a team effort: it’s not about individual skill, but about working with capable partners to create something unforgettable. My motto is to make others look their best, and if they do the same, together we can make a truly memorable scene.”

Wushu Goals & Future

Dario looks forward to competing at the 17th World Wushu Championship in Brazil. “I’m very excited,” he says. “It will be the penultimate event of an endless year: when I return, I have national championships, but competing in Brazil with top athletes gives me the energy to compete for another hundred years. Wushu in Brazil has grown tremendously, with very high-level athletes, and my Brazilian friends are outstanding. I will always thank them for their support, advice, and friendship. I can’t wait to see how the hosts welcome their guests. I trust it will be another unforgettable competition.”

“Wushu saved my life,” states Dario, “and if it were a person, I’d hug and thank it for being there during my most difficult and fragile moments. It allowed me to avoid school problems, because doing well academically meant I could train all I wanted. In daily life, it helps me stay agile and athletic, and more importantly, it shields me from negative influences, stress, and the world’s chaos. Learning to breathe and relax, I don’t know the tension or “anxiety” everyone talks about—thanks to wushu. If I’m traveling or waiting for hours with nothing to do, I close my eyes and think of my taolu, and I start sweating; no Netflix, music, or phone needed: I’m free!”

“I hope,” Dario says, “to remain competitive in wushu for another ten years, then focus on traditional wushu, and at around one hundred years old, practice taiji for another twenty… then I’ll slow down. I hope to participate in the Olympics, wishing that by 2032 in Brisbane, wushu will finally be part of the Games. I want to leave my mark, making the sport spectacular in my way. I may never jump as high as others—but I’m still looking for a signature trait to be remembered by. I continue experimenting with a smile, hoping one day to be recognized even just for my unique “kung fu” style. I hope to contribute with many ideas to promote wushu worldwide.”

Following the Dream

Dario concludes, “Life, sport, and wushu have taught me that nothing is impossible if you have passion, courage, and a little madness to chase your dreams. To those reading: don’t be afraid to be different, to feel strange, or to take a path few choose. The world will always have people saying you can’t… but they cannot know how big the fire inside you is. Train, laugh at your mistakes, surround yourself with people who believe in you, and never stop playing—because even the hardest competitions are a great game that makes us free. I will continue practicing wushu as long as I have breath in my lungs, and I hope that one day, someone watching me will think: “If he did it, I can too.” That is the greatest legacy an athlete can leave: inspiring others to believe in themselves.”